St Paul’s Cathedral is THE building which Londoners see as the symbol of their city and it has been the venue for dozens of important national events over the centuries. This post re-tells a few of them, plus the story of its master architect, Christopher Wren before detailing some of the highlights to look out for when you visit. King Charles summed up its importance as a historical venue, a beautiful building and a place of worship. St Paul’s, he wrote, is ‘not just a mausoleum for national heroes, it is also a temple which glorifies God through the inspired expression of man’s craftsmanship and art.’

st paul’s: the beginnings

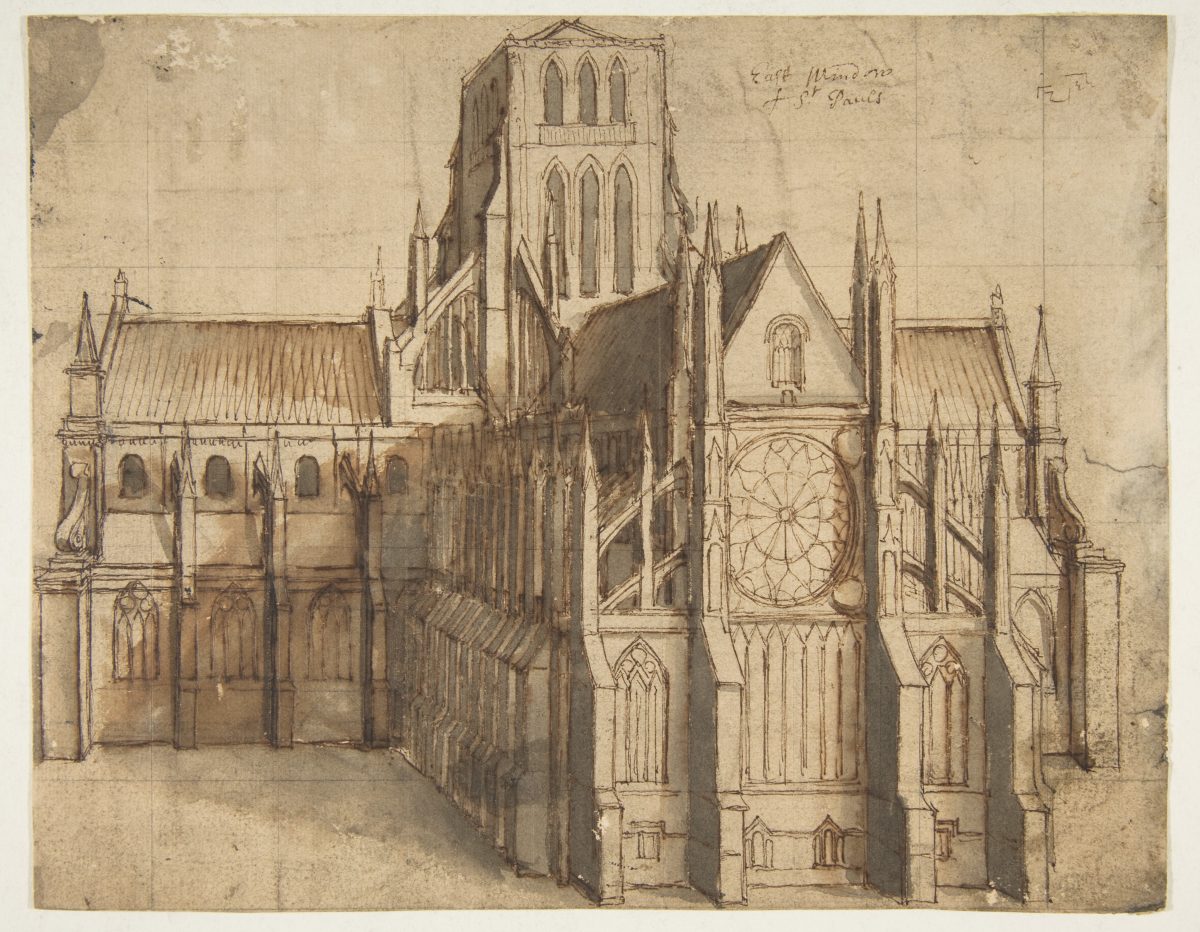

This is the 5th major church on this site. The first, built by Bishop Mellitus, a missionary sent from Rome, in 604, burned down, the second was destroyed by the Vikings, the third burned down and the 4th, built by the Normans was the largest Christian church in Europe, bigger than the current one in fact. Known today as Old St Paul’s, it too burned down in the Great Fire of London in 1666, at which point King Charles II commissioned the architect Christopher Wren to design a glorious new version.

Old St Paul’s

The medieval St Paul’s, the Norman one, was famed throughout the city because of the outdoor pulpit, known as St Paul’s Cross, where news was broadcast to those who gathered to hear it. It was a noisy place, where traders gathered alongside prostitutes, card tricksters and all manner of beggars and crooks. In 1501 it was here that Catherine of Aragon married Prince Arthur, the older son of Henry VII – and brother to Henry VIII, who married her after Arthur’s death. Observers described Catherine’s Spanish style wedding dress and wrote of the jubilant celebrations which followed: ‘banquets, disguisings and jousting.’ In 1588 Queen Elizabeth I attended a thanksgiving service after the defeat of the Spanish Armada.

Old St Paul’s was originally catholic, so worship centred on the veneration of saints, mass, shrines and the observance of Feast Days. Then came the Reformation. In 1521 the Pope’s sentence against Luther was read out here, denouncing him for he ‘erred sore and spoke against the holy faith’. Copies of William Tyndale’s New Testament Bible in English were burned in the courtyard. But by 1536, the year of Anne Boleyn’s execution, the Bishop of Durham spoke here, denouncing the Pope and offering prayers for Henry VIII as ‘the onelie supreame head of this realm of Englande’. After that the choir sang in English, not Latin and the Book of Common Prayer was used. St Paul’s was now protestant.

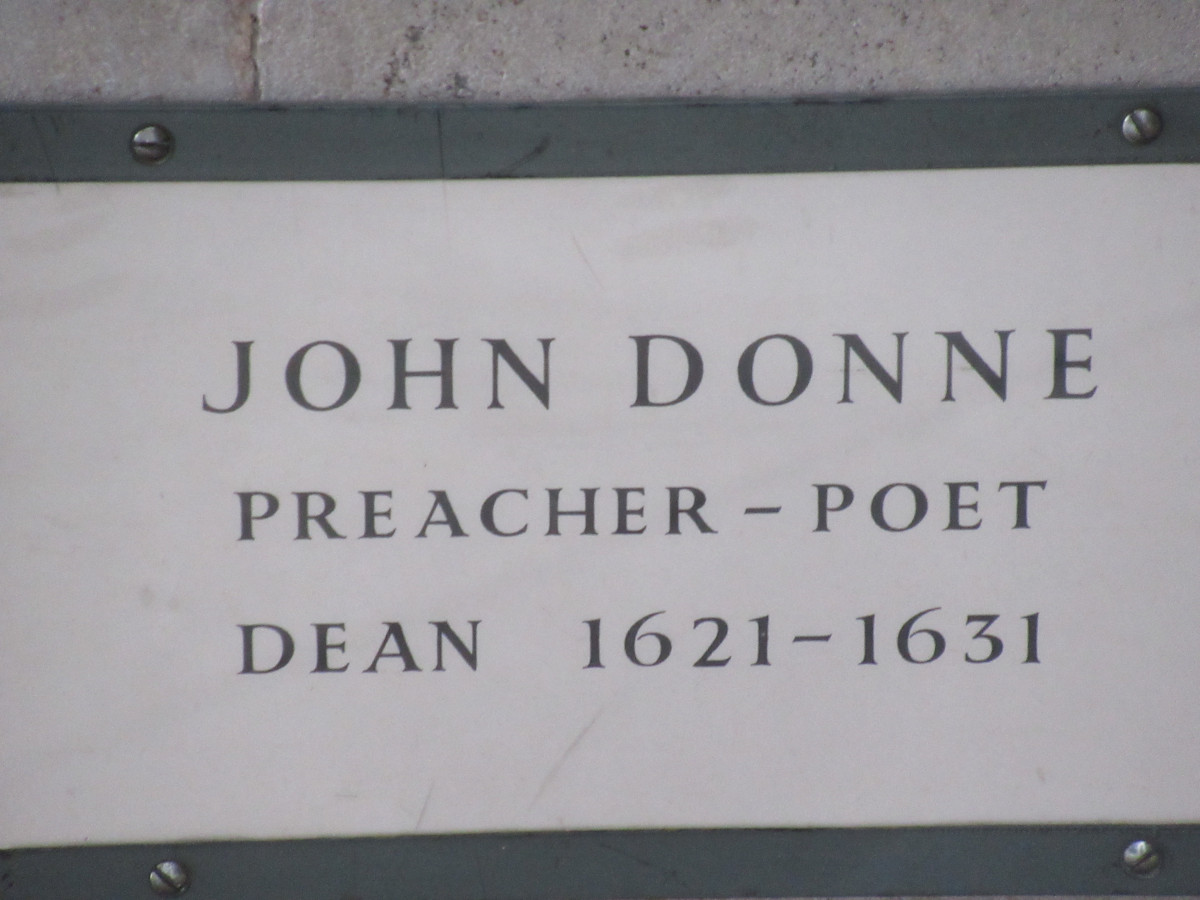

The poet John Donne was Dean of St Paul’s for a decade in the 1620s. During the English Civil War in the 1640s, St Paul’s was used as a barracks for the cavalry and even as stabling for horses. After the restoration, King Charles was considering having it renovated, but in 1666 came the devastating fire and, as the diarist John Evelyn wrote, Old St Paul’s was completely destroyed: ‘thus lay in ashes the most venerable church, one of the ancientest pieces of early piety in the Christian world’. The cathedral, alongside two thirds of the city of London and over 80 other churches, would have to be rebuilt.

sir christopher wren

St Paul’s was therefore the first protestant cathedral to be built in England. Christopher Wren was appointed ‘Surveyor of the King’s Works’ and laid the foundation stone in 1675. Early in the rebuild, a workman happened upon a broken piece of gravestone engraved with the Latin word ‘Resurgam’, or ‘I shall rise again’ in English and this became the motto of the project. From the ashes, a new, spectacular building would rise up. In fact, a contemporary described the stunning finished building, so familiar on today’s London skyline , as ‘a matchless pile’.

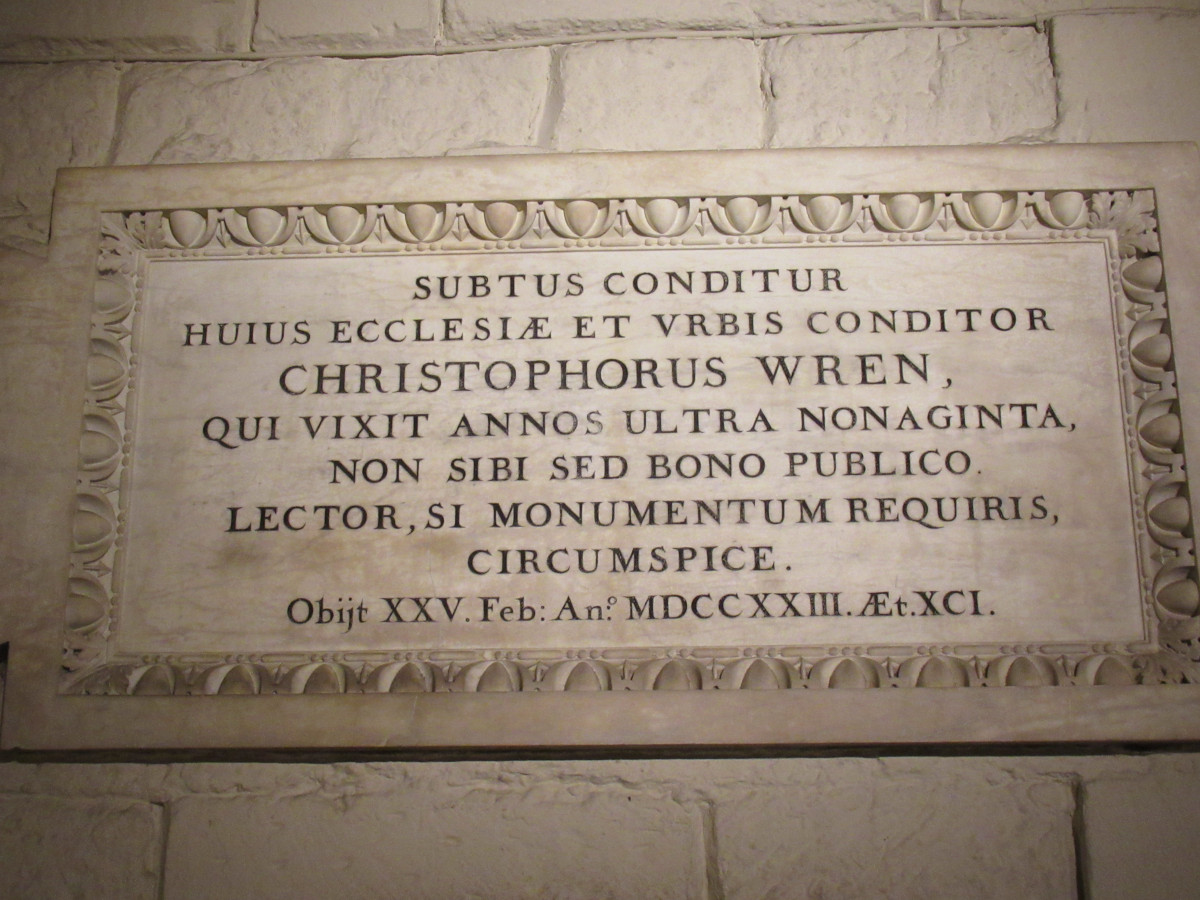

Christopher Wren had read admiringly of the domes of Florence Cathedral and Istanbul’s Haga Sophia and worked out a design for St Paul’s. Above the inner dome, beautifully painted, is a sturdy brick middle layer supporting the stunning outer dome that would become the cathedral’s best-known feature. Wren liked to visit the dome regularly until his death at the age of 91 and to sit under dome and reflect. Fittingly, he is buried in the crypt where you can read the words chosen by his son to emphasise his father’s achievement: ‘Lector, si monumentum requires, circumspice.’ In English, ‘Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you.’ There’s more on the building of St Paul’s on the podcast.

famous moments at st paul’s

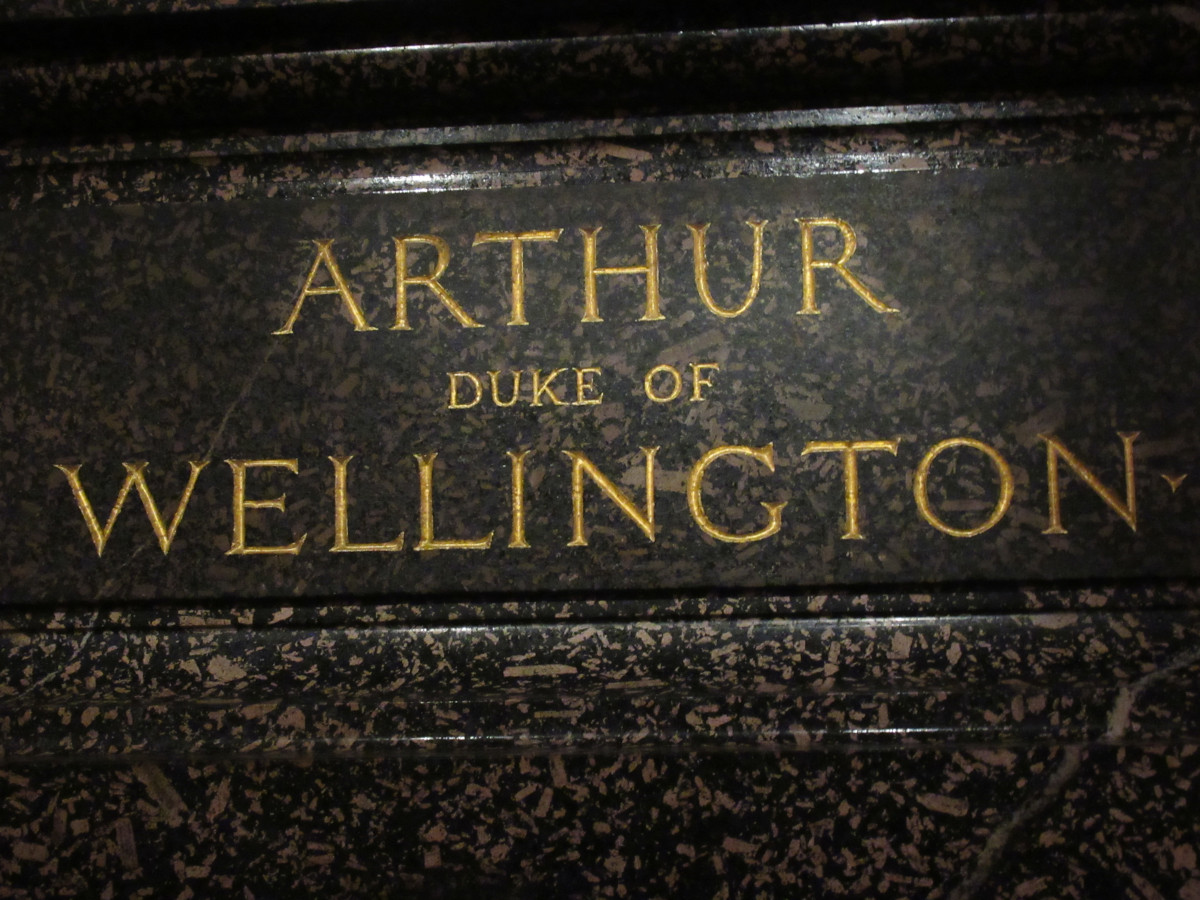

On St George’s Day, 1789, a service was held here in thanksgiving for the return to health of King George III. Ever since Nelson’s funeral in 1806, when he was buried in a coffin made from the mast of a French ship, a ‘Sea Service’ is held on the nearest Sunday to Trafalgar Day. For the Duke of Wellington’s funeral in 1852, there was a procession of 10,000 people, led by Prince Albert, to accompany his funeral carriage, pulled by 12 horses, to St Paul’s. Special stands were set up inside so that 13,000 people could attend.

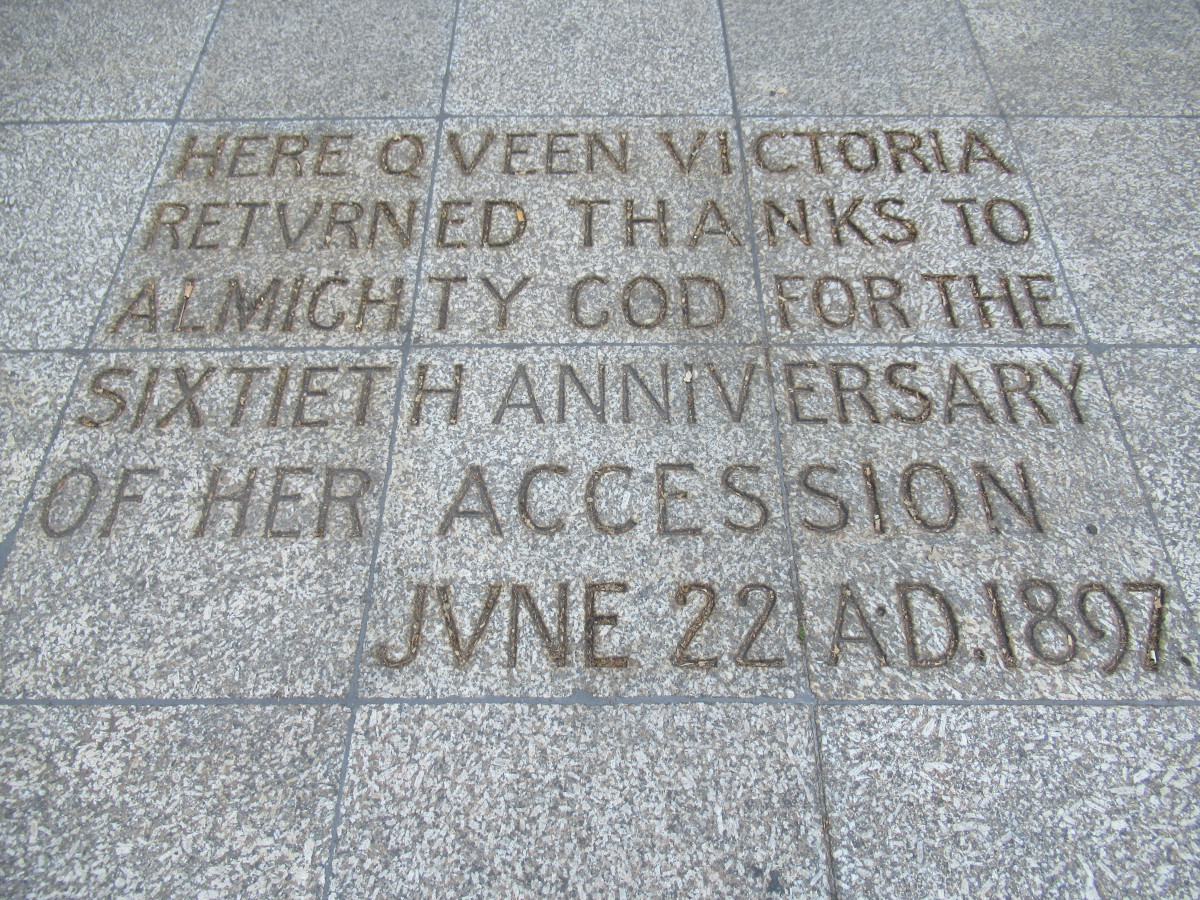

The service for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 was held on the steps of the cathedral as she was deemed too frail to leave her carriage. It ended with an unexpected, but rousing, ‘three cheers’ led by the Archbishop of Canterbury. It was at St Paul’s that crowds chose to gather to mark the end of the First World War and in World War Two, the cathedral became a symbol of London’s survival during the Blitz. Herbert Mason’s photograph of the unscathed dome, silhoutted against the sky and surrounded by flames and fire damage, went around the globe. On VE Day in 1945, 30,000 people gathered spontaneously at St Paul’s and 9 services of thanksgiving for peace were held.

In 1965, for ‘Operation Hope Not’, the funeral of Sir Winston Churchill, cameras were installed inside the cathedral for first time, and 900 million people watched it worldwide. On the podcast, there is more detail on the service, the procession and the military flypast which were part of the event. Prince Charles married Lady Diana Spencer at St Paul’s in 1982, and later services of thanksgiving were held for all three of Queen Elizabeth II’s Jubilees – Golden, Diamond and Platinum – in 2002, 2012 and 2022 respectively. It was outside St Paul’s that crowds gathered after the 9/11 bombings in New York and the London bombings in July 2005. Yet again, St Paul’s seemed to be the heart of the nation.

what to look out for

The main worship area, including the altar, is under the dome. Look out for the many memorial plaques, including a group of British artists such as Turner, Constable and Blake. The most unmissable statues include those of Nelson – a cloak obscures his amputated arm – the Duke of Wellington, John Donne and Samuel Johnson. There is a relief depicting Florence Nightingale. Inside, you can visit the Whispering Gallery, running all around the inside of the dome and, if you have someone with you, try out whispering to each other from opposite sides. Outside, there are two galleries to visit, the Stone Gallery and – the highest outside point you can visit – the Golden Gallery, for which you need to climb 528 steps!

The American Memorial Chapel pays tribute to 28.000 Americans killed in Britain during World War Two, their names listed on a 500 page roll of honour kept behind the altar. Downstairs in the crypt are many tombs, including those of Nelson, Wellington and Sir Christopher Wren. On the cathedral’s front, a relief depicts the conversion of St Paul to Christianity and a statue of Queen Anne, the reigning monarch when the building was completed. In the courtyard is a plaque marking the location of St Paul’s Cross, alongside a gilded statue of St Paul. The two bells are justly famous – Great Paul, older than the cathedral itself, and Great Tom, which tolls to mark the death of the sovereign.

Listen to the POdcast

Reading suggestions

St Paul’s, The Story of the Cathedral by Ann Saunders

Sir Christopher Wren by Paul Rabbitts

links for this post

Previous episode Introduction to London

Next episode The City of London

Last Updated on November 21, 2024 by Marian Jones