‘In the dust scattered in Santa Croce is written the history of Italian civilisation’, explains the church’s guide book. So yes, Santa Croce, which means Holy Cross, is one of Florence’s most important buildings and this post tells a little of its history and then outlines the main things to look out for when you visit: one of the city’s most important artworks plus tombs and memorials for some 270 of Italy’s best-known artists, politicians and scientists.

a little history

The foundation stone of this Franciscan church was laid in 1294 in a ceremony which, according to a chronicler who was there, was conducted ‘with great festivity and solemnity’, in the presence of ‘many bishops and all the good people of Florence.’ By 1320 it was nearly finished, but delays and disasters, including catastrophic flooding in 1333 and the plague which ravaged 14th century Florence meant that it was not consecrated until 1453. It has 3 naves, separated by stone pillars, 2 cloisters, a large refectory, a bell tower and a number of exquisite chapels, paid for by some of the 14th and 15th century’s wealthiest Florentine families: the Medici, the Velluti, the Tolosini, the Pazzi and others.

famous tombs and memorials

Santa Croce is Florence’s equivalent of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral, or the Pantheon in Paris, that is the place where some of Italy’s most famous people are buried. And none is better known than Michelangelo, who died in Rome, but who had left instructions that he should be buried in Florence, even if that meant smuggling his body into the Tuscan capital. The artist Giorgio Vasari, a contemporary, wrote movingly of the candle-lit ceremony held to entomb Michelangelo’s remains here, describing the ‘very grand and imposing spectacle’, attended by black-clad mourners and many of the city’s best-known artists. Vasari himself designed the statue for the tomb, a bust of Michelangelo surrounded by 3 statues representing painting, sculpture and architecture.

When the politician and philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli died in 1527, he was interred here without honours because he was despised by the authorities. Much later, in 1878, a monument was erected to honour him, inscribed with the highest praise: ‘Tanto nomini nullum par elogium’, or ‘For so great a man no eulogy is sufficient’. Galileo, the brilliant 17th century astronomer and physicist whose work so angered the church was refused a Christian burial until 95 years after his death when his body was finally moved to a marble sarcophagus here. Dante, the city’s most famous literary figure is buried in Ravenna, where he died in 1321, but a monument to him stands proudly outside the main entrance to Santa Croce.

artworks to look out for

As so often in big churches, the glorious artwork can be overwhelming. Perhaps it’s best to just wander first, from chapel to cloister and take in the beauty. Then, what to focus on? At Santa Croce, there are some of Donatellos’s best-known works including his gilded sculpture, The Annunciation, a beautiful carving of the intimate scene when the angel visits Mary to tell her that she is carrying the son of God and also a wooden crucifix portraying the dead Christ on the cross.

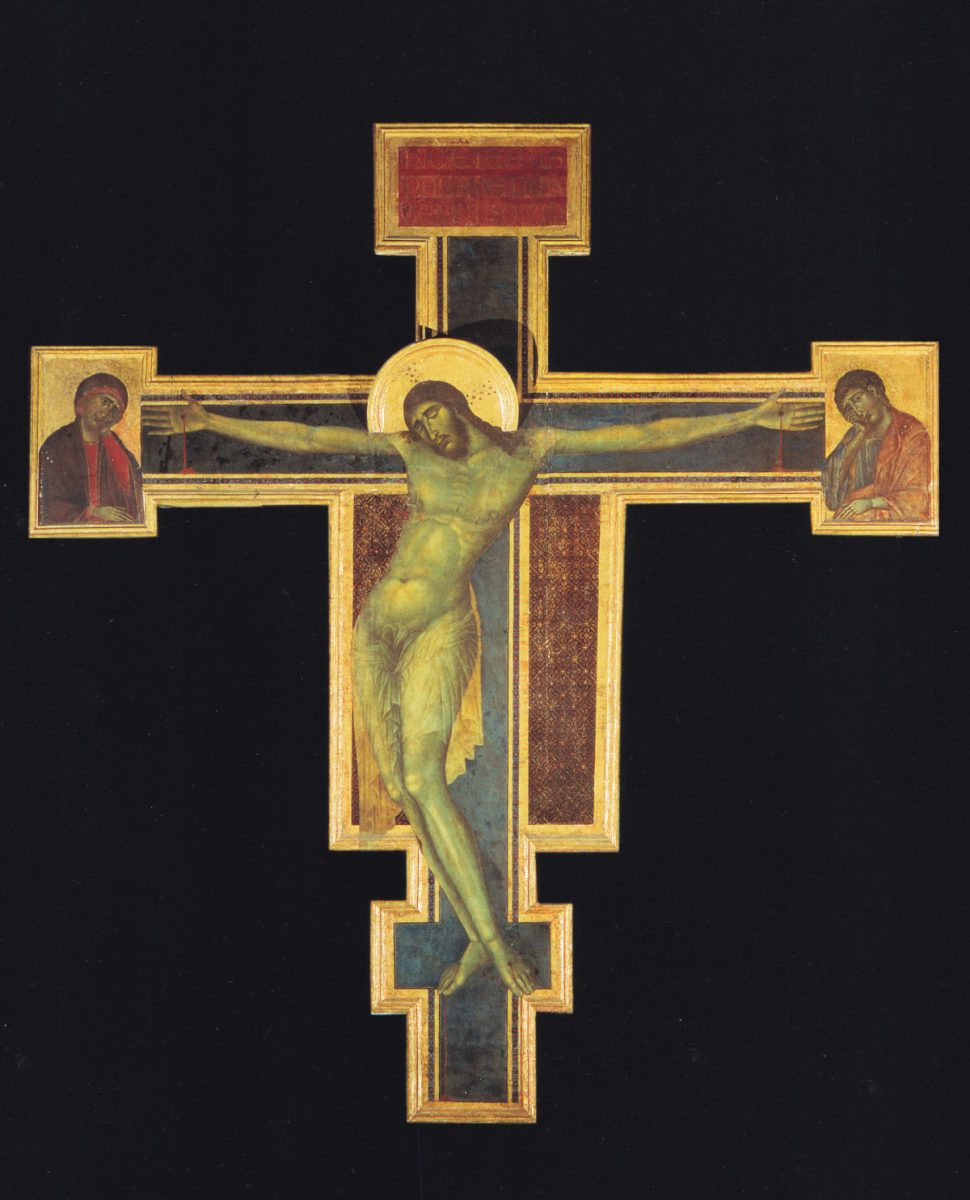

Best known of all is a crucifix by Cimabue, made in about 1280, a large painted wooden cross which is famous for two main reasons. First, it is a moving depiction of Christ in agony at Calvary, a portrayal of human suffering which has inspired artists across the centuries. And secondly, it has become a symbol of hope, representing the way Florence fought back from the floods which devasted the city in 1966. Cimabue’s cross was submerged and then, like so many of the city’s other treasures, rescued and restored.

the floods of 1966

Catastrophic flooding had twice hit Florence on November 4th, in 1333 and in 1844. In 1966, the world watched it happen yet again. Along with 30 other churches in the city, Santa Croce was badly damaged, its square left submerged under 9 feet of filthy water from the River Arno. Across the city, where it is estimated that ‘a ton of flood mud for every man, woman and child in the city’ was left behind, millions of precious documents and artworks were rescued by volunteers, many of them young art students from across the world, who became known as the ‘Mud Angels.’ A huge restoration project was begun and within 20 years, two thirds of the damage had been repaired.

Cimabue’s crucifix was one of the artefacts which was saved. Today it is displayed high up on a wall in the museum section of Santa Croce, some damage still visible, but nevertheless a defiant symbol of the city’s recovery from disaster. The city authorities have taken many steps to prevent a recurrence. New reservoirs and a dam have been built, all precious artworks are stored above street level and regular flood drills are held. Cimabue’s crucifix, now nearly 8 hundred years old, is protected by an electric pulley system which will, if necessary, raise it up further and keep it out of harm’s way.

piazza santa croce

This lovely square has long been a gathering place for Florentines to witness important events in the life of the city. In the 15th century they watched Giuliano and Lorenzo di Medici jousting here. Large crowds also came to hear Franciscan monks preaching as, for example, in 1633 when they read out a ‘letter of gratitude’ to the Virgin Mary because the horrors of the recent plague had abated. Not long after the unification of Italy, King Vittorio Emmanuele II himself visited in 1885 to witness the inauguration of the statue of Dante. After the terrible floods of 1966, Pope John Paul VI visited the square and the church of Santa Croce to show solidarity with the afflicted citizens.

In her novel The Birth of Venus, Sarah Dunant describes this square in the 16th century as bustling with cloth traders who made their living by importing fabric, then dyeing, treating and exporting it. The area, near the river, she writes, was ‘jammed with slum houses … children splattered with mud and steaked with colour from stirring the vats’. It was also the scene, in 1530, of the first Florentine soccer game, a tradition which continues today and is known as ‘Calcio Storico’, or ‘historic football’. There is more on the podcast about this mad and violent game, which teams from across the city named, for example, Santa Maria Novella, San Giovanni, Santo Spirito and Santa Croce, still play today.

Listen to the POdcast

Reading suggestions

Florence, the Biography of a City by Christopher Hibbert

The Birth of Venus by Sarah Dunant

links for this post

Link for this post

Santa Croce

Previous episode Dante’s Florence

Next episode Santa Maria Novella

Last Updated on June 11, 2023 by Marian Jones