Fleet Street has been a focal point for writers, publishers and journalists since the Middle Ages. This post explores a little of its history during the 19th and 20th centuries when the area was home to almost every national newspaper. We also cover what there is to see here, from the pubs frequented by famous writers and journalists across the centuries, to two places of interest which are open to the public: the home where Dr Johnson wrote his famous dictionary and St Bride’s Church, known as the spiritual home of the media.

a little history

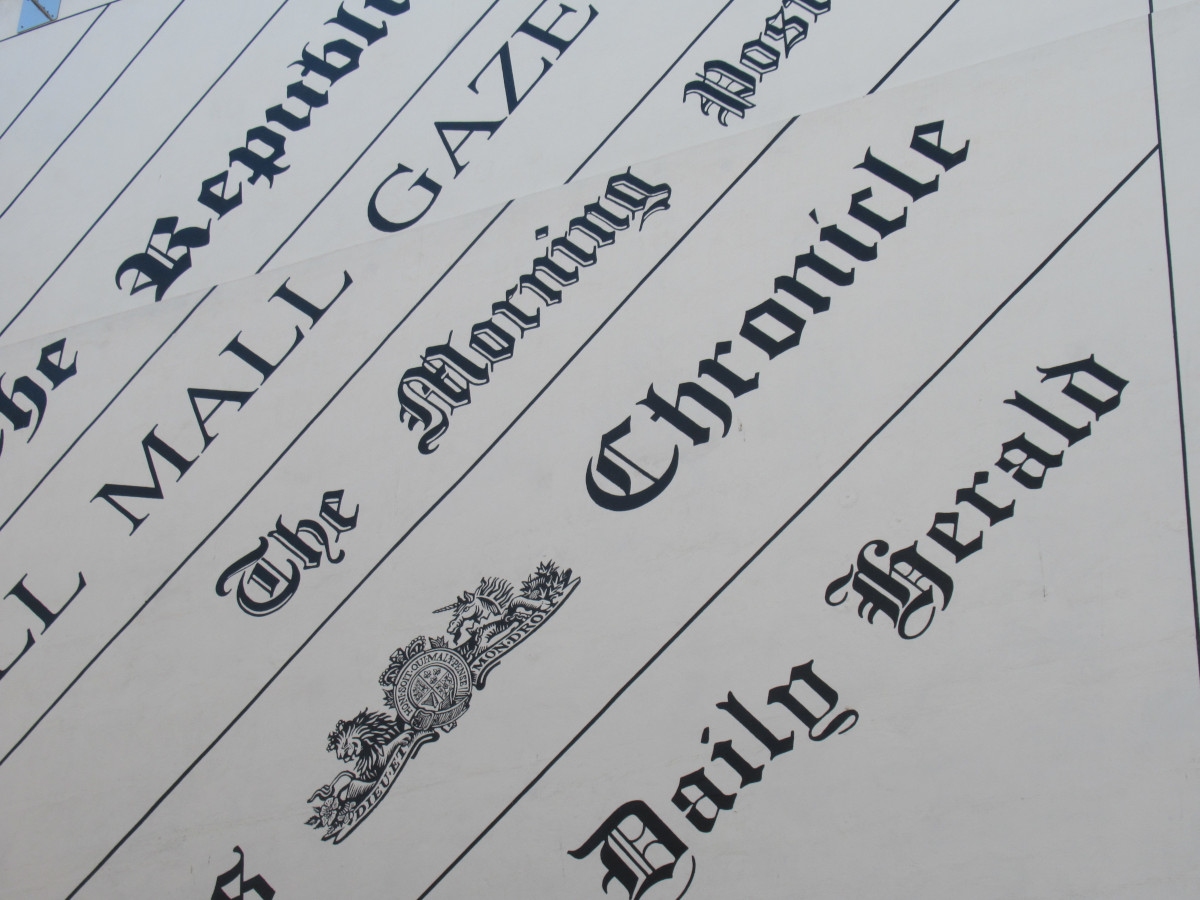

Publishing started in the Fleet Street area in 1500, when William Caxton’s apprentice, the wonderfully named Wynkyn de Worde, set up a printing shop here. In March 1702, London’s first daily newspaper, the Daily Courant, was published in Fleet Street. Things really took off in the 19th century when Paper Duty and Newspaper Tax were both abolished, making newspapers cheaper to produce. A high point was reached when the ‘penny press’ was born in the 1880s. By the 20th century, Fleet Street dominated the national press and more than 25 different publications had their HQ here, including the Daily Express at no 121-8 and the Daily Telegraph at no 135-42.

But in 1996, amid much controversy, Rupert Murdoch moved his News International titles, such as The Times and The Sun, out to Wapping, leaving printing behind and switching to digital technology. A year of violent protests followed as the print unions objected to the resulting job losses, but ultimately the die was cast and other publications also left Fleet Street for Canary Wharf and Southwark. Today Fleet Street is more about investment banking and the legal profession, but some vestiges of his newspaper history remain.

fleet street’s famous pubs

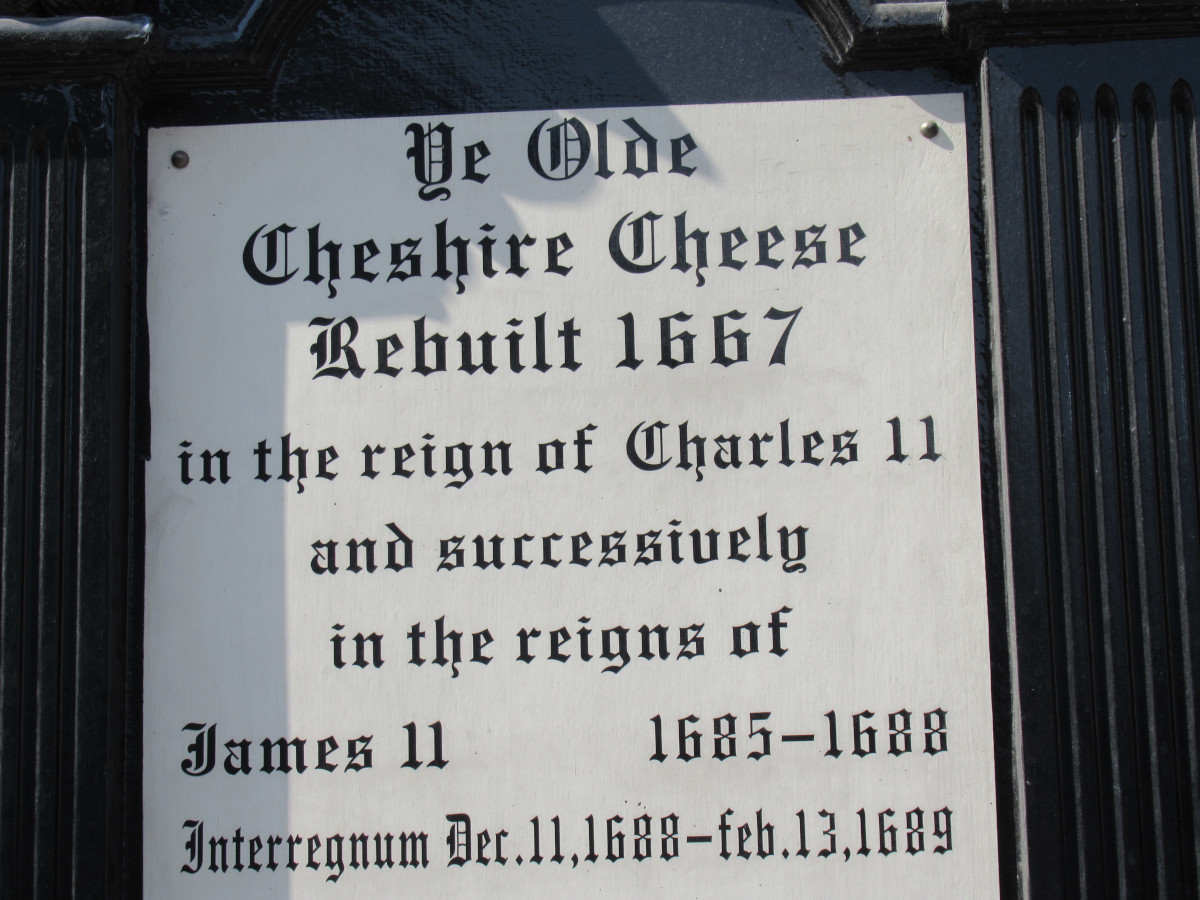

Journalists have long gathered at Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese at no 145 Fleet Street, the first city building to be rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666. Outside it, a board lists the 15 monarchs who have reigned since it was first opened. This Grade II listed building was a favourite of such famous authors as Charles Dickens and P G Wodehouse. It’s known for its gloomy interior and is described as follows in Christopher Winn’s London by Tube. ‘Its brown glass windows and creaking dark wood-and-sawdust décor is highly atmospheric’. Another journalists’ favourite, The White Hart at 3, New Fetter Lane, just off Fleet Street (now closed) was known colloquially as ‘The Stab in the Back.’

There is more on the podcast about the many famous writers who lived, worked and drank in Fleet Street over the centuries.

read all about it

Among the many books written about Fleet Street, perhaps the best-known is Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop which satirises the profession mercilessly. For example, a novice journalist, Jakes, falls asleep on a train to the Balkans and then invents ‘a thousand-word story about barricades in the streets’. Although things ‘seemed quiet enough’, he ‘filed a thousand words of blood and thunder a day’ until the inevitable happened: ‘in less than a week there was an honest-to-god revolution underway, just as Jakes had said. That’s the power of the press for you.’

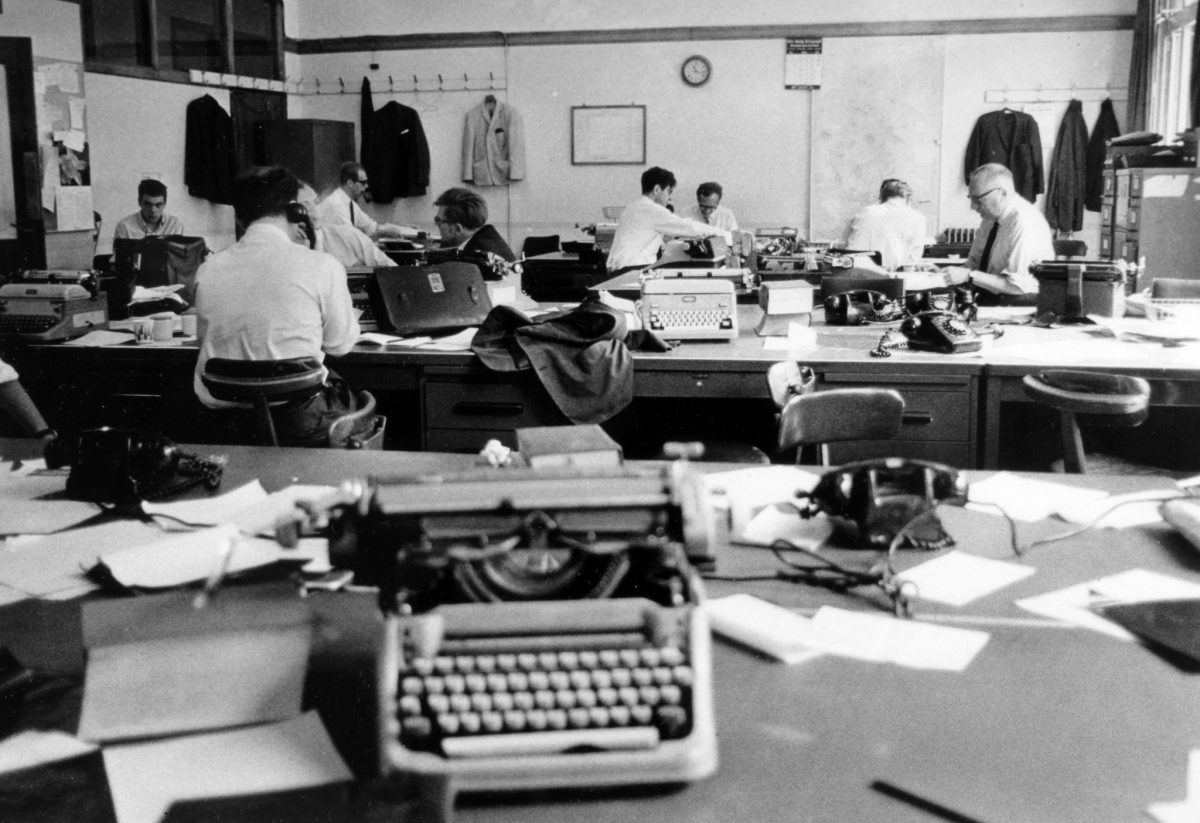

Michael Frayn’s Towards the End of the Morning is a humorously exaggerated description of journalism in Fleet Street’s dying days. This quotation gives a flavour and explains the title! ‘Various members of the staff emerged from Hand and Ball Passage during the last dark hour of the morning, walked with an air of sober responsibility towards the main entrance, greeted the commissionaire and vanished upstairs in the lift to telephone their friends and draw their expenses before going out again to have lunch.

Liz Hodgkinson’s Ladies of the Street covers the story of the few, yet intrepid women who worked in Fleet Street in its heyday and, as the Amazon review puts it, ‘blasted their way into jobs previously reserved exclusively for men’. She describes how the few female journalists all worked in one room, known as ‘the Piranha Pool’ and relates how ‘I was working on an undercover job once for a paper and rang an editor from a payphone, to check in with him. He asked ‘Are you in danger, pet?’ I replied ‘Yes I am.’ To which he replied ‘Oh, good.’

Julie Welch’s The Fleet Street Girls also tells the tale of the female journalists’ battle for equality in Fleet Street in the 1970s and 80s. She describes the strike demanded by National Union of Journalists when she, as a ‘mere secretary’ dared to write an article, even though men who were not journalists had done the same. She also remembers some of the other trail-blazing women who worked alongside her in the struggle to change Fleet Street from a cosy all-male club when, as a reviewer puts it, ‘the interests of half the human race were consigned to ‘the Women’s Page.’

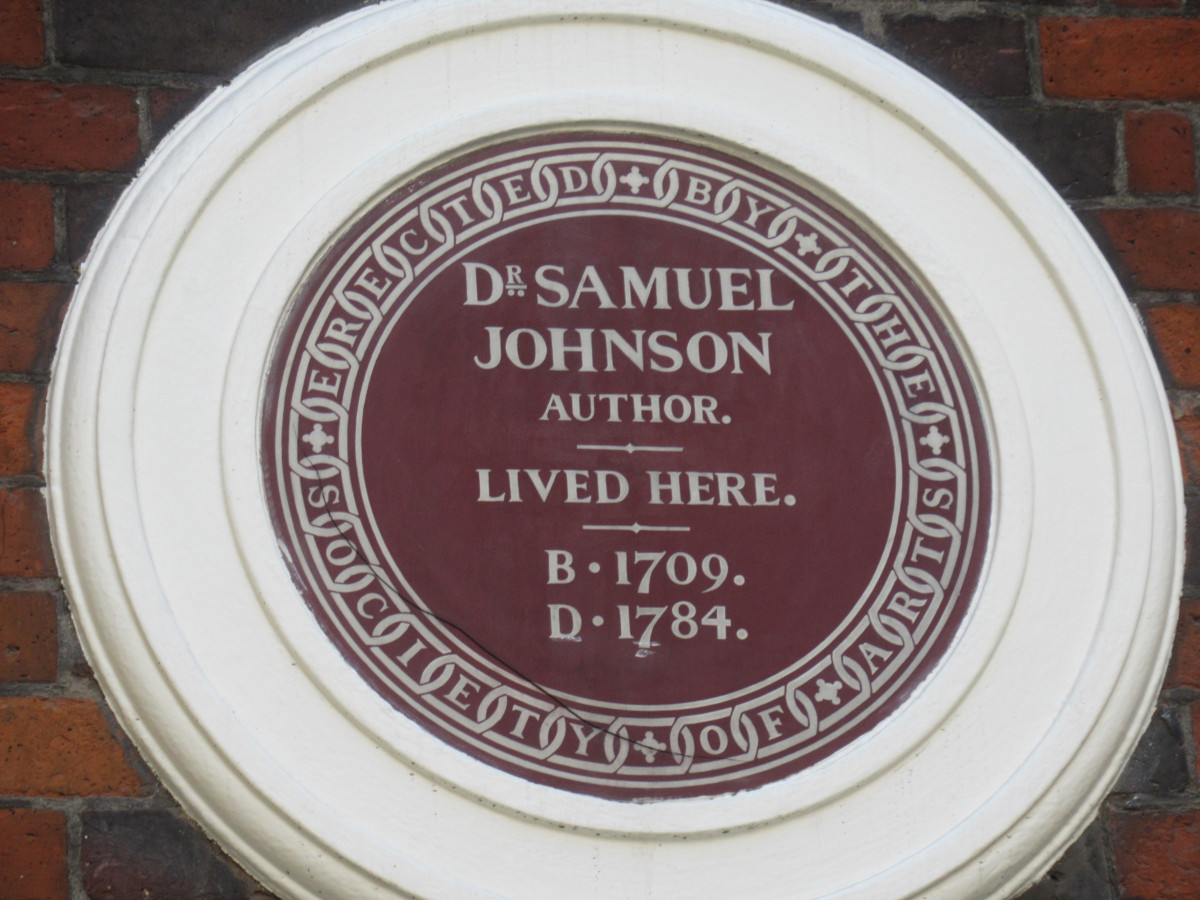

dr johnson’s house

Dr Johnson’s House is the elegant 300-year-old townhouse where Samuel Johnson lived and worked, producing his famous dictionary in 1755. It’s in Gough Court, just off Fleet Street and it’s open to the public. Here you can learn about Johnson and his work through paintings, manuscripts and memorabilia and visit the rooms he lived in, including the attic where he toiled for 9 years, along with 5 assistants, to produce the influential dictionary which far surpassed anything of the kind published before that.

Johnson was a prolific writer, producing a stream of essays, poems, pamphlets, biographies and works of literary criticism. There’s more on the podcast about his life and works, but he is eminently quotable. He famously commented ‘No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money’. He noted that it took 40 members of the Académie Française 40 years to produce a comparable dictionary to his, done so much more quickly by a handful of scholars and said this illustrated ‘the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.’ But he could be modest too. Challenged on how he’d let a mistake through to the finished work, he explained the reason was simply ‘ignorance, pure ignorance.’

Do look out for the statue of Johnson’s ‘very fine cat’, Hodge, sitting outside the house with his favourite treat of oysters.

st bride’s: the journalists’ church

St Bride’s, known as ‘the journalists’ church’ is another Fleet Street institution. There has been Christian worship on this site for 2000 years, and this church, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, is the 8th version. Many authors had connections to St Bride’s: Samuel Pepys was baptised here, Milton lived in a house in the courtyard and the 17th century diarist John Evelyn worshipped here. The Journalists’ Altar was first so called during the 1980s when vigils were held there for the journalist John McCarthy, kept as a hostage in Beirut for 4 years. There are memorials to other journalists who have been killed while reporting the news and memorial services are often held for journalists and other media figures.

St Bride’s has the highest spire ever built by Sir Christopher Wren apart from that at St Paul’s. The story of how it’s said to have inspired the first tiered wedding cake ever baked is told on the podcast. Other things to look out for include links to the story of the American colonies – some of the Pilgrim Fathers had connections to St Brides. There is a Roman mosaic and accompanying exhibition in the crypt and the remains of a medieval chapel, discovered when the present church was built in the 17th century, were restored in 2002.

Listen to the POdcast

Reading suggestions

London by Tube by Christopher Winn

Scoop by Evelyn Waugh

Towards the End of the Morning by Michael Frayn

Ladies of the Street by Liz Hodgkinson

The Fleet Street Girls by Julie Welch

Samuel Johnson, A Biography by Peter Martin

Dr Johnson’s London by Liza Picard

links for this post

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese

Dr Johnson’s House

St Bride’s Church

Previous episode The Inns of Court

Next episode The Strand and Piccadilly

Last Updated on November 21, 2024 by Marian Jones