Visit Edinburgh’s New Town, built in the 18th century, and you’re in the seat of the Enlightenment, in the elegant streets and squares to which the wealthy escaped, very happy to leave the squalor of the Old Town – Aule Reekie! – behind. This post gives a little history and explains what to see when you visit the New Town, including The Georgian House Museum where the era comes to life. Finally, there’s a brief rundown of Edinburgh during the Enlightenment period when William Smellie, editor of the first Encyclopaedia Britannica, marvelled that he could stand at the Mercat Cross and ‘in a few minutes, take 50 men of genius and learning by the hand.’

a little history

During the 18th century, plans began in to take shape for building a smart ‘new town’ in Edinburgh, on land reclaimed by draining away flood waters to the north of the castle. The architect James Craig’s design was chosen and three elegant parallel main streets – Princes Street, George Street and Queen Street – were built, with a beautiful square at each end, Charlotte Square and St Andrew Square. In a later phase in the 1820s, came more beautifully proportioned streets, such as Drummond Place and Royal Circus and in the 1830s, the Moray estate, with a cluster of crescents, ovals and octagons around the 12-sided Moray Place.

The well-to-do – lawyers, doctors, military men and colonial entrepreneurs – soon made plans to build large sandstone mansions in this part of town and by 1830 it was a very congenial place to live. The Assembly Rooms were built for concerts, readings and charity balls, the original Theatre Royal opened on Princes Street in 1769 and most people found the orderly regularity of the architecture a thing of beauty. There were critics too, such as Lord Henry Cockburn who found the long straight streets dull, disliked the ‘rectangular intersections’ and complained that ‘every house is an exact replica of its neighbour’.

charlotte square and st andrew square

These two garden squares are integral features of Edinburgh’s New Town. The beautiful St Andrew Square was designed by James Craig in the late 1760s and it is open to the public. Charlotte Square was designed in the 1790s. by Robert Adam, the most celebrated architect of his day. No 6 is Bute House, the official residence of Scotland’s First Minister and no 7 houses The Georgian House Museum. The 4 sides surround the Charlotte Square Gardens, not usually open to the public, which is dominated by the enormous statue of Prince Albert on horseback, commissioned in tribute to him after his death and paid for by public subscription. Queen Victoria herself attended its unveiling in 1876.

the georgian house

This museum is the place to find out all about life in Georgian Edinburgh, for it has been carefully restored to recreate the comfortable home where wealthy families lived a very congenial existence, supported by their numerous servants. Rooms to visit include the drawing room, where the family entertained guests and the dining room where sumptuous three-course meals were served. There is a parlour too, which was more of a family room used for needlework, reading and writing letters and where the children might be brought by the nursery maids to spend a little time with their parents. There’s also a study for the man of the house (!), where he could retire to think enlightenment thoughts undisturbed.

Much is done to explain what all this shows about life in Enlightenment Edinburgh. The menu for a dinner party shows a first course (soup, fish, fowl and vegetables) followed by a main course of ‘game, fowls, pies, cheeses, sweets, cakes, jam and puddings’ and then dessert, which was likely to include apples, pears, nuts, figs, dates, almonds, raisins and oranges. The guests ate all this by candlelight, then the ladies retired to the drawing room leaving the men to their port. Later, the men would join them, perhaps for backgammon or chess, to hear the ladies play the piano or sing or, on occasion, for a little dancing to a small group of musicians.

But the portable water closet, dating from 1805, is a reminder that facilities were basic. It’s a wooden chair, with a large hole in the middle and a copper bucket underneath. A brass handle operates the flush, for which the water would need to be supplied in buckets, a task which – along with emptying the bowl – would fall to the housemaids. And the long list of servants shows that for every person living in relative luxury in the main house, there were several more working hard to maintain their pleasant life. The butler and the housekeeper were in charge of cooks, kitchen and scullery maids, housemaids and, if there were children in the family, nursery maids.

the enlightenment

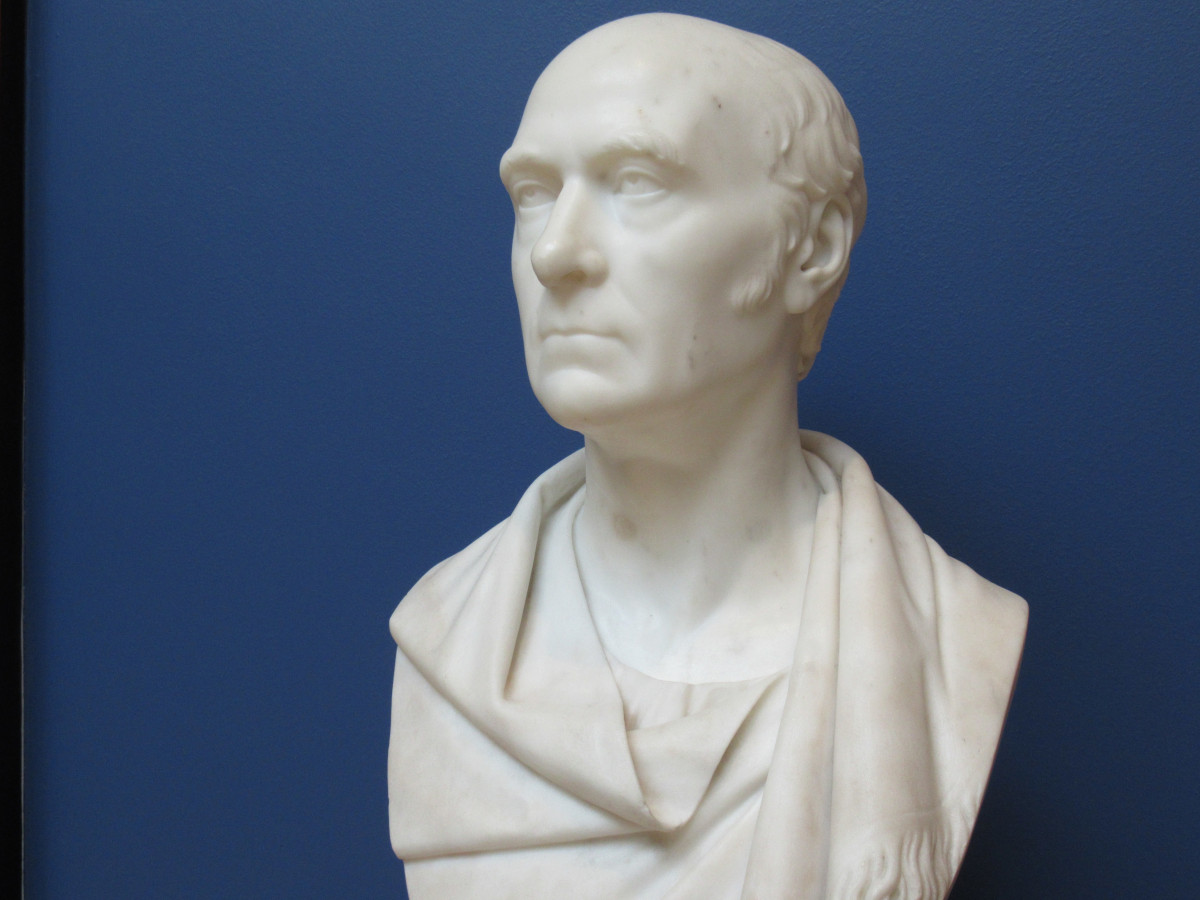

The Enlightenment was Europe-wide, but it flourished particularly in Edinburgh, where a whole host of thinkers, artists and scientists lived and worked in the 18th and early 19th centuries. They include the philosopher David Hume, the political economist Adam Smith, the architect Robert Adam, the artists Henry Raeburn and Alexander Nasmyth and the author Walter Scott. Statues of many of them can be found in the city today, for example on the Royal Mile (David Hume, Adam Smith) and in Princes Street Gardens, where a statue of Walter Scott (and his dog) sits inside the enormous Scott Monument. The portraits of many of Edinburgh’s Enlightenment thinkers hang in The National Galleries of Scotland Portrait Gallery in Queen Street.

The respected Edinburgh Review, founded in 1802, was published for over a century, and the city’s university, although founded in the 16th century, flourished particularly during the Enlightenment and its reputation spread throughout Europe. This was also the era of the salon, when the intelligentsia gathered in the drawing rooms of Edinburgh’s New Town for discussions and literary events. Much has been written on what the men said to each other, but the women get less of a mention. Two who were named in journals written at the time were the society hostesses Mrs Apreece and Mrs Waddington, one admired ‘for the vivacity of her conversation’ and the other ‘for her remarkable beauty and the grace of her manners’.

Listen to the POdcast

Reading suggestions

A History of Edinburgh by Christopher McNab

Edinburgh, A History of the City by Michael Fry

The Scottish Enlightenment by Arthur Hernan

The Scottish Enlightenment: an Anthology by Alexander Broadie

links for this post

Links for this post

The Georgian House

The National Portrait Gallery

Previous episode Auld Reekie, Edinburgh’s Old Town

Next episode The Two Scottish Parliaments

Last Updated on November 21, 2024 by Marian Jones