Bloomsbury, London’s literary and academic heartland, is full of pretty garden squares and the place to find some of the country’s top museums, bookshops and libraries. We stroll past many of them, pointing out some historical and literary connections, especially those relating to the Bloomsbury Group and then explore what else there is to see in this little area which is the very essence of Englishness, a quietly elegant corner of the capital.

a wander through bloomsbury

Let’s start with 3 of the best-known squares, which are conveniently close together – Bloomsbury, Bedford and Russell Squares. Bloomsbury Square was the first official square in London, built in the 1660s. By the 18th century, wealthy families were occupying 3 sides while their servants were housed on the 4th. Famous residents include British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, as a child, at no 6 and Gertrude Stein who lodged here in her brother’s house from 1902, conveniently close to the British Library where she spent much of her time.

Bedford Square is London’s only remaining complete Georgian Square, built in the 1770s on land belonging to the Duke of Bedford. Its style was something new as every house was designed in the same style around a central garden. In the 1910s Lady Ottoline Morrell lived here and ran a famous literary salon attended, for example, by D H Lawrence, Lytton Strachey and the poet T S Eliot, whom Lady Morrell pronounced ‘dull, dull, dull’. In the 1980s it was home to several major publishing houses including Jonathan Cape and Bodley Head and today it is the still registered address of Bloomsbury Publishing of Harry Potter fame.

Russell Square – where the nightingale reputedly sang – bears the family name of the Dukes of Bedford and is Bloomsbury’s largest square. It too has a definite literary flavour, for Faber and Faber were here for decades, employing T S Eliot and publishing, for instance, the poets W H Auden, Stephen Spender and Ted Hughes, although they rejected George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Scandal hit in the 1930s when a woman paced the pavement outside wearing a placard which read ‘I am the wife that T S Eliot abandoned’. Eliot did, however, sleep at the office on fire-watch during World War II.

more bloomsbury squares

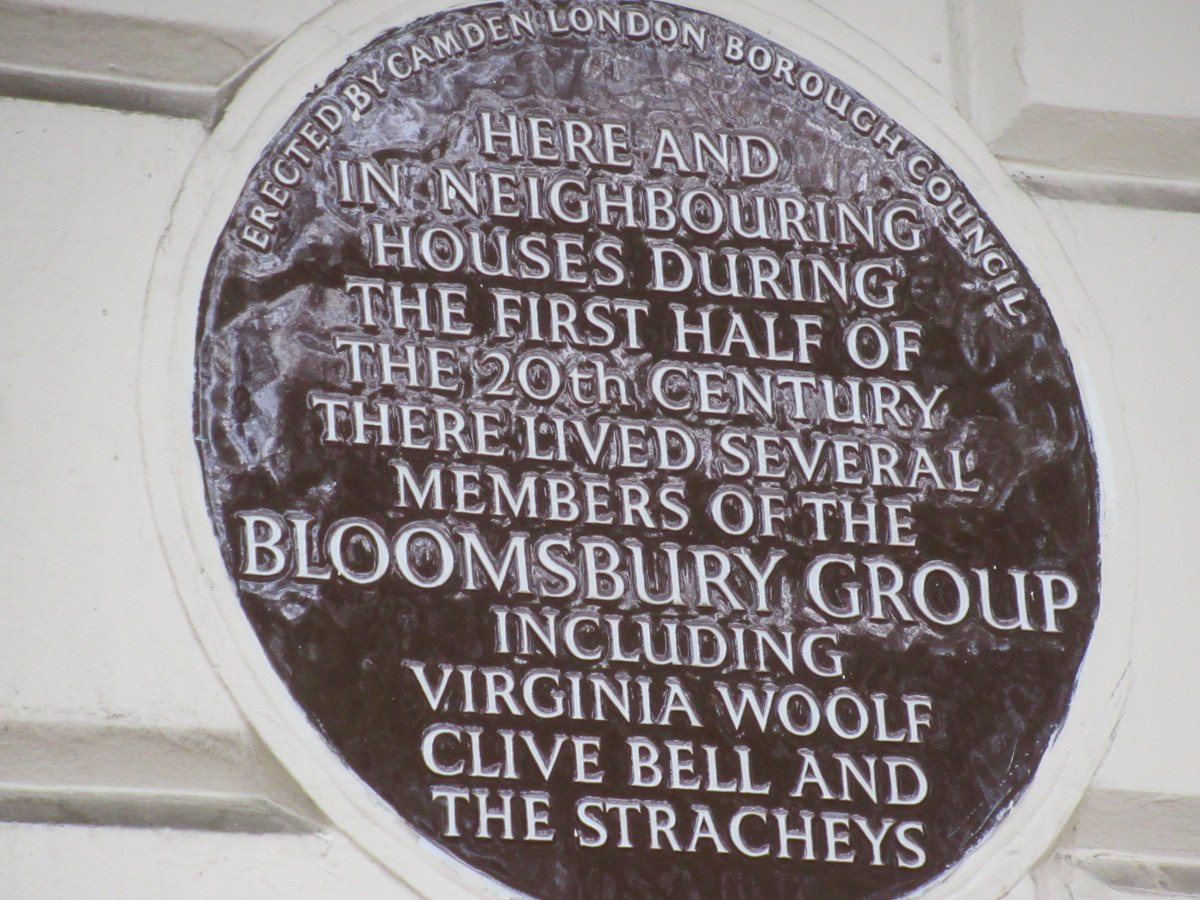

Queen Square was named after Queen Anne in 1720, while Brunswick Square, which had to be largely rebuilt after WWII, is named after George IV’s wife, the former Caroline of Braunschweig (Brunswick in English). Many of the Bloomsbury Group lived here, including Virginia Stephens, later Woolf, John Maynard Keynes and E M Forster. Jane Austen’s fictional character Isabella (in Emma) loved it, saying ‘We are so very airy. I should be unwilling to live in any other part of town.’ Mecklenburg Square was named to honour Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, who had been the Princess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Virginia Woolf lived here too, as did D H Lawrence, while writing Women in Love.

46 Gordon Square was the venue for the first Bloomsbury Group meetings from 1904 and all 4 of the Stephens siblings including Virginia (later Woolf) and Vanessa (later Bell) lived there. Today the square is owned by the University of London, although the central garden remains open to the public. Charles Dickens lived in Tavistock Square while writing a number of novels including Bleak House and Hard Times. No 32 was yet another of Virginia Woolf’s homes, where she wrote most of her novels, but it was destroyed in the Blitz in 1940. There is a bust of her in the central garden, along with one of Mahatma Gandhi who studied Law at University College London in the 1880s.

the bloomsbury group

The Bloomsbury Group originated in 1899, when Thoby Stephens – brother of Virginia and Vanessa – formed a secret society with a few fellow students at Trinity College, Cambridge. After they graduated, they continued to meet, holding discussion groups in Thoby’s London home in Gordon Square and joined by his two sisters. The group included some of the most radical thinkers and artists of their time and gained a reputation for plain speaking, however controversial one’s thoughts. Virginia admired Lytton Strachey for ‘his honesty of mind’ and the way he enjoyed ‘poking fun at any sham’.

Key members of the group included Virginia and Vanessa’s husbands, author and publisher Leonard Woolf and Clive Bell, author and art critic. Lytton Strachey, author of the ground-breaking biography, Eminent Victorians, went on to write many books and essays. Duncan Grant was a bold, experimental artist and Vanessa Bell also made her name as a painter. John Maynard Keynes came to prominence with his prescient book The Economic Consequences of the Peace, about the Treaty of Versailles and went on to write many books and academic papers and also to spearhead the creation of the Arts Council of Great Britain.

But it was Virginia Woolf who became the best known of all. The stream-of-consciousness style of novels such as Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse was fresh and new, mirroring the thoughts of the character as the story unfolds. For example, a moment when Clarissa Dalloway is walking through London to buy flowers is described thus: ‘June had drawn out every leaf on the trees. The mothers of Pimlico gave suck to their young. Messages were passing from the Fleet to the Admiralty. Arlington Street and Piccadilly seemed to chafe the very air in the park and lift its leaves hotly, brilliantly on waves of that divine vitality which Clarissa loved. To dance, to ride, she adored all that.’

The Bloomsbury Group were also known for the complex web of their relationships and their fluid sexuality. Amy Licence referenced this in the title of her book about them, Living in Squares, Loving in Triangles. An example is her description of Duncan Grant’s love life: ‘Predominantly homosexual, he had been engaged in an affair with his cousin Lytton, whom he had left for the Apostle John Maynard Keynes, before falling in love with James Strachey, who was in turn enamoured of Rupert Brooke, after which Duncan became enamoured of Cambridge scientist Arthur Hobhouse. It was a complicated emotional tangle, peppered by brief flirtations with women, which often left Duncan uncertain and unhappy. By 1907, he was involved again with Keynes.’

There is much more about the Bloomsbury Group on the podcast.

bloomsbury for book and museum fans

The British Museum is the big attraction. With its several million objects from every part of the globe, it’s the world’s largest museum of human history and culture. If you’re unsure where to start, consider doing a ‘highlights tour’ with a guide, or checking the list of tours available on the day you visit, which could be anything from Japanese artefacts to culture in Roman Britain or Ancient Iraq. The British Library also stages exhibitions, or you can visit to look round and see highlights like the glass-walled tower in the entrance hall which contains all the books donated by King George III. Bloomsbury is full of interesting bookshops, such as The London Review Bookshop and Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers.

There is much more on what there is to see at the British Museum and the British Library on the podcast.

More evidence of the area’s academic credentials are its connections to the University of London. At University College London in Gower Street there are two museums open to the public – the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology and the Grant Museum of Zoology. Look out too for Senate House in Malet Street, not open to the public, but interesting because it was used as the Ministry of Information during World War II and inspired George Orwell, who worked there, when creating the Ministry of Truth for his novel 1984. When opened in 1936, it was described as a ‘bleak, blank, hideous building’.

Listen to the POdcast

Reading suggestions

The Bloomsbury Group by Frances Spalding

Living in Squares, Loving in Triangles by Amy Licence

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf

links for this post

The British Museum

The British Library

The London Review Bookshop

Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers

Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

Grant Museum of Zoology

Previous episode London and Charles Dickens

Next episode The East End and the Docks

Last Updated on November 21, 2024 by Marian Jones