Neither Fontainebleau nor Vaux-le-Vicomte has featured yet in our Paris series, but they are two of the blockbuster sights. Granted, you have to leave the city to see them, but both are reachable in no more than an hour and between them they offer architectural splendour, significant moments of history, fascinating characters and captivating stories. So, this episode brings you a taste of all of that, plus some handy advice on how to get to each. As ever, there is MUCH more detail on the podcast.

Fontainebleau

Take a 40-minute train ride from the Gare de Lyon in central Paris to Fontainebleau-Avon, then a bus from outside the station, or a 30-minute walk will get you to the splendid château ruled over by every French king from the 12th to the 19th century. Many of them left their mark, which explains the higgeldy-piggeldy mish-mash of the château’s architecture: medieval turrets, a largely renaissance façade, Napoleon’s initials in gold on the gates. There are sights to see and tales to tell from all of these eras and here are just a few. There are more on the podcast.

Medieval prestige and Renaissance splendour

Fontainebleau, already a popular country destination with kings who loved to hunt, got its Royal Charter in 1137 and as one King Louis built a chapel here and another Louis installed a church and a monastery, it grew in importance. King Francis I (1515-47) brought renaissance splendour, especially to be seen in the Gallery of Francis, connecting his apartments to the monastery next door and lavishly decorated with intricate walnut panelling and gilded carvings of his initial, F, the fleur-de-lys symbol of French royalty and his personal emblem, the salamander. Francis wore the only key to the gallery around his neck and allowed only a favoured few to go inside.

His son, Henri II, (1519-59) not to be outdone, created the magnificent ballroom where the embellishments range from gilded H’s all over the ceiling panels to bronze copies of classical Roman statues and a musicians’ gallery. Look out too for the intertwined H and D lettering, paying tribute to Henri’s mistress, Diane de Poitiers. Descriptions of court life on the podcast include derring-do hunting exploits and an insight into renaissance court entertainment with its feasting, jesters, jigs, masque balls and filles de joie.

Grand Designs and a Revolution

Henri IV (1589-1610) added the splendid Oval Courtyard, installed a Jeu de Paume court and had a 1200 metre long Grand Canal built in the grounds 60 years before Louis XIV did the same at Versailles. His mother, Anne of Austria, regent when he became king at only 4 years old, redesigned the Queen Mother’s Wing, leaving her initials all over the ceiling and in the Queen’s Bedchamber you can see fine objects made of mother of pearl, gilded bronze, satin and ebony chosen by Marie-Antoinette. Much is missing though, having been looted or auctioned off during the revolution which led to her downfall.

napoleon

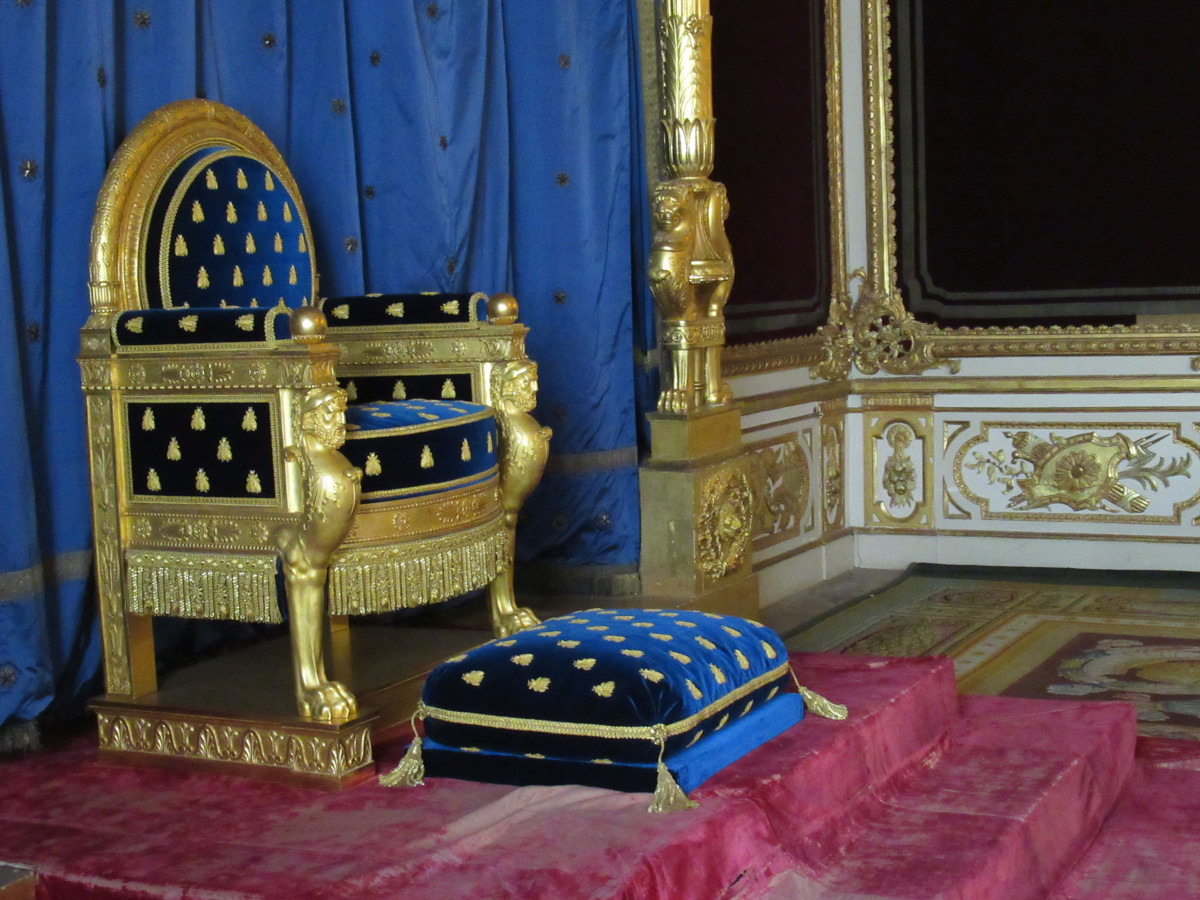

Oh, the irony. Napoleon installed himself as Emperor not much more than a decade after the French revolution. At Fontainebleau, where he was often in residence, he transformed the former King’s Bedroom into a Throne Room, decorated with his personal emblems, the imperial eagle and the letter N and installing a throne brought from the Tuileries Palace. But Fontainebleau was also the scene of his demise and you can still see the Salle d’Abdication where he signed away his power and the horseshoe staircase in the courtyard where he made a dramatic last address to his soldiers which began ‘I bid you farewell. For twenty years, you have constantly been by my side on the road to honour and glory’.

Here too is the Museum of Napoleon, where you can browse such memorabilia as portraits, medals, souvenirs from his military campaigns and even a gold leaf from the crown he wore during his coronation.

the 2nd empire

After a few more decades of monarchy, the Second Empire of Napoleon III (nephew of you-know-who) and the Empress Eugénie followed. Traces of them can be seen in her ‘Lacquer Salon’ where she collected the Asian art she loved and his 400 seat theatre. After their empire fell in 1870, Fontainebleau was closed. It had various uses in the 20th century, as a wartime military hospital and NATO headquarters and was then restored as a heritage site and opened to the public. It was also at Fontainebleau that the French national equestrian team trained for the 2024 Paris Olympics.

vaux-le-vicomte

You can get to Vaux-le-Vicomte by train from the Gare de Lyon in central Paris. Alight at Melun, then in summer you will find a shuttle bus to take you to the château just a ten minute drive away. Otherwise, there are plenty of taxis outside the station.

It’s definitely worth it – this might be the most beautiful château in the entire Paris area. When Madame de Montespan, one of Louis XIV’s mistresses, was invited to a party there, she was entranced and wrote a diary entry about it which began: ‘On reaching Vaux-le-Vicomte, how great and general was our amazement ….. it was a veritable fairy palace.’ Ask AI today for details and it waxes eloquent about its luminous limestone exterior and the ‘breath-taking visual’ of its symmetrically designed gardens, their pools and statues, their boxwood parterres and grand vistas. No wonder then, that Louis XIV chose it as his model for Versailles. Inside it is crammed with marble and paintings, with statues and gilded furniture.

And yet, the most interesting thing about Vaux-le-Vicomte is the story behind it, truly a tale of triumph swiftly followed by disaster. It was all the dream of one man, Nicolas Fouquet, Chief Superintendant of Finances to Louis XIV, who spent all his considerable wealth building it. He hired the very best architect (Louis Le Vaux), garden designer (André Le Nôtre) and artist (Charles le Brun) and told them money was no object. He wanted un ravissement pour les yeux, that is a ‘delight to behold’ and they obliged. Then he invited the king and all his court to come and admire it and planned the most stupendous party to impress them. That’s when it all went wrong.

It was August 17th, 1661. Serenaded by 24 violins, Le Fouquet’s guests ate a lavish meal of many courses at which the host had ordered his chef to dazzle the king with ‘the audacity, harmony, rarity, opulence and richness of the food served.’ Then it was out into the gardens for music, a play written specially for the occasion by Molière and a firework extravaganza which lit up the gardens in all their splendour. The writer Jean de la Fontaine, a guest, later wrote that ‘Vaux never looked more beautiful than it did on that evening.’ But, Louis was livid. He accused Le Fouquet of trying to outshine him, snapping ‘As far as I’m aware, it is I who am king.’

The full story, told in much more detail on the podcast, is also one of political intrigue and the jealousy of some of Le Fouquet’s rivals, but the short version is that he was tried, found guilty of ‘maladministration and lese-majesté and imprisoned for the rest of his life. As Voltaire summarised it all later, ‘At 6 in the evening on the 17th August, Fouquet was king of France; at 2 the next morning, he was a nobody.’

It is said that Le Fouquet spent the last 19 years of his life in prison, reminiscing about the beautiful château he had left behind. Louis, au contraire, promptly confiscated much of the artwork, furniture and even the plants from the garden and commissioned the trio of masterminds, Le Vau, Le Nôtre and Le Brun to design something even more fantastic for himself. Work on the château of Versailles began immediately and, just 20 years later in 1881, it opened as the main royal residence for its creator, Louis XIV.

Listen to the POdcast

Reading suggestions

Louis XIV, Real King of Versailles by Josephine Wilkinson

King of the World The Life of Louis XIV by Philip Mansell

links for this post

Previous episode Fiction set in Paris

Next episode Vincennes and St-Germain-en-Laye

Last Updated on March 4, 2026 by Marian Jones